In 2001, following regulation of the organic industry in the USA, Michael Pollan wrote ‘Behind the Organic-Industrial Complex’.[i] It was an accurate insight into the food industry’s move to brand organic. The market blog anticipated the same thing happening here. Well, that time has arrived. Here we discuss the recent move to regulate the word ‘organic’ in NZ, MPI’s conflicts of interest, the slippery slope of industrial organics, and the problems of the mainstream, the effect on local food enterprise and the export focused agri industrial food system.

Industry grab

The national umbrella organisation Organics Aotearoa New Zealand (OANZ) has been pushing for organic regulation for more than a year as a way to ‘protect certified organic producers’. Brendan Hoare, the chairman of OANZ, made the claim in a 2015 Stuff press release that there was widespread abuse of the term ‘organic’ in New Zealand, suggesting that consumers of products advertised as organic are unwittingly eating food tainted by chemicals. He went on to say "There are restaurants claiming organic, there are all sorts of ranges of products saying they've got organic ingredients - there's no third party verification required,” and “We get examples of this all the time - or it could be local growers claiming organic produce at farmers markets."

The Ministry for Primary Industries (MPI) are now assisting in the move to regulate the organic industry as the agribusiness industry starts to take notice of the opportunities there. MPI put the proposal, to regulate use of the term ‘organic’, to the public in June this year. As a consequence you may have noticed the media attention this is now getting. [i] MPI have been given the onerous task of policy maker. MPI promote and police all kinds of agribusiness including conventional agriculture and horticulture, meat and dairy. They act as both regulator and champion of primary industries. Their purpose, as stated on their website, is to help “maximise export opportunities for our primary industries, improve sector productivity, ensure the food we produce is safe, increase sustainable resource use, and protect New Zealand from biological risk”. It is easy to see a conflict of interest between their role of regulating industry practices while working to maximise export opportunities.

Media releases also assist in how we as consumers and citizens understand this issue. In the following image, farmers markets are misleadingly presented as being synonymous with the organic sector.

”New Zealand’s organic sector is worth an estimated $500 million”. May 16 2018 Stuff.co.nz

Throwing farmers markets into the mix

Unsubstantiated comments can also be misleading too like the OANZ chairman’s quote about farmers markets and restaurants claiming to sell organic products. Such claims, however, are likely to be insignificant compared with the examples of breaches of trust from industry food producers.[ii] It beggars belief why they were even singled out in this discussion. Including farmers markets into the mix is essential for an agri business image: food industry giants quash any competition no matter how small.[iii] [iv] With unlimited budgets spent on promotion and on consumers, the most obvious place to start is on the vernacular. Local, fresh, farm to plate, farmer, market and organic are now supermarket speak. It would be naive to think that press releases consciously or not do not reflect agribusiness influence. [v] After all, food is big business. Organic supermarket sales were $216m for the year to May 2018, but only add up 2.2 percent of total supermarket sales – specialty stores sold $30m worth of organic products. New Zealand supermarket sales (general) for 2017 were $6.2 billion, an increase of 2.1 percent from last year.[vi]

Authentically local

Farmers markets and the better restaurants are usually the epitome of local and fresh. In New Zealand they are still a mostly weekend discretionary activity and, despite the apparent success of some, markets can struggle against the odds with little assistance at a regional or national level. I find it hard to imagine how regulation of the word ‘organic’ will benefit small producers who live and work within the local food networks. This is regulation designed for agribusiness, and a new brand for its distributors. The distinction between this and local food networks needs to be made. Leave the markets and their stallholders out of any organic regulation.

OANZ are, it would seem, the poster child for agri- food business. Integrity has already been lost there.

But not all is lost. Soil and Health, who have undergone significant governance changes as a result of the move by agribusiness supporters into organic branding, said quite rightly in their submission that they want a “proviso that the regulation must not disadvantage small scale producers”. [viii] [ix]

The arguments that support the regulatory approach: Export, trade, feeding populations

The export trade is central to this regulatory approach, as is the assumption that it leads to economic prosperity. NZ needs to comply with the other countries’ standards in order to strengthen the trade and export of organics, we are told. Incidentally we still await country of origin legislation. [x] Trade treaties are so powerful that they effectively [xi]operate like de facto global governments. Australia and New Zealand are the only countries in the industrialised western world who have yet to follow the USA by adopting an organic certification system on a national level. The assumption is that it is a necessary requirement. The consensus amongst industry leaders is that NZ needs to get into step with the likes of the USA, Canada, the European Union and Japan, who have similar regulatory laws. This trade paradigm is based upon such things as agri chemicals, breeding, crop production (farming and contract farming), distribution, farm machinery, processing, and seed supply, as well as marketing and retail sales. With the dominance of industry scale food production it makes total sense that some form of regulation is needed to protect citizens from food industry corruption in the form of false claims and inadequate food labelling.

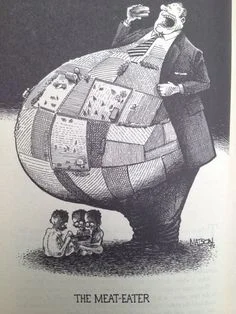

Regulation, unsurprisingly, has its supporters in the food industry including the dairy, beef and big box food distributors.[xii] Heavily subsidised infrastructure allows goods produced on a large scale and transported long distances to be sold at artificially low prices - in many cases at lower prices than goods produced locally.[xiii] Redundant trade is when countries export and import the same foods. Helena Norberg Hodge, a localisation advocate, informs us that in a situation of runaway climate change and dwindling fossil fuels such redundant trade needs reanalysis.[xiv] Trade has become an end in itself. After decades of prolific, damaging, and inhumane industrial farming, subsidies for the largest and wealthiest farms and support for associated research, we have been left with a cut throat retail food environment dominated by a handful of corporations: this is the mainstream.

Transnational corporations, who are largely responsible for the bulk of processed foods we consume, are often recipients of significant economic development subsidies. This is certainly the case in the USA. Yet small food independents (businesses, producers, farmers and growers) catering for local and domestic communities can struggle to survive. These small industries seldom receive any subsidies or any policy that works in their favour. Local growers struggle to compete with the cheaper industry scaled growers. Legislation is also largely influenced by big businesses who lobby the government committees that create policy. [xv] To quote a controversial environmentalist Vandana Shiva; “the right of corporations to force-feed citizens of the world with culturally inappropriate and hazardous foods has been made absolute. The right to food, the right to safety, the right to culture, are all being treated as trade barriers that need to be dismantled…we have to reclaim our right to nutrition and food safety. Food democracy…is the new agenda for ecological sustainability and social justice.”[xvi] But MPI would say this is beyond their scope.

Unchallenged assumptions about trade and agribusiness make any change within the system difficult. Policy makers need to challenge the belief that we need industrial scale food production at all costs and that genetic modification is essential for superior food production. Science, like religion, can be hijacked by those with an ulterior motive.

The real cost: the environment, climate change, health

What more convincing do we need to understand that the food system is broken? The signs are here, everywhere. Environmental effects of animal agriculture and the health perils of having to consume cheap food are a direct result of subsidising the industrial production of foods.[xvii] Although New Zealand agribusiness may receive less subsidies than countries such as the USA, it still externalises those costs all the way along the food line from the chemicals that are used to grow it, the pollution it creates, to the poor health of the consumers who purchase it. [xviii] Trade embargoes and other political wrangling are the most significant contributors to third world starvation.[xix] We now know that the true cost of cheap food is actually far greater than we are led to believe. When a country continues to measure its success by its Gross Domestic Product it fails to take into account these other relevant factors. But we end up paying for it. The existing model of food production and distribution has resulted in the mess which supporters of regulated organics claim will now save us. [xx] [xxi] [xxii] [xxiii]

MPI’s Food Safety has little to do with the health of the populous. So it is not surprising that MPI had previously claimed with reference to organics that there was no "serious risk to the health and wellbeing of consumers or to (existing) trade" from lack of regulation. So are they up to the task? The chair of OANZ said New Zealand industry listens to the global market. Shouldn’t we take this as a warning! He went on to say that “Consumers want change, so they can live their values, producers and farmers are seeking change to do what is good for the land they love, and global markets are demanding greater and greater choice as organic goes mainstream”.

The problem with the mainstream

Supermarkets are the mainstream. They control the retail food industry and especially so in NZ with the duopoly between Food Stuffs and Progressive Enterprises. They operate like cartels and dictate purchasing prices from growers. They influence regional and governmental policies.[xxiv] In the United States large food companies have "assumed a powerful role in setting the standards for organic foods”. Supermarkets and processed food in particular represent the extremes of the food industry; cheap food, super convenience, plastic and more plastic despite consumers resistance.[xxv] Supermarkets turn our communities into food deserts. Big box supermarkets actually limit food choices by putting anyone who competes with them out of business. They operate as butcher, baker, fishmonger and grocer, and even coffee shops and petrol stations. Is this really good town planning?

Isn’t the mainstream the problem?

If there was any truth in the rose tinted statement by Hoare that “Consumers increasingly want their purchasing practices to reflect their ethical values, or their social values, or their political values,” and as he suggested recently “there was a national and global mood for change to natural, ethical, sustainable food and other daily used products”, then doesn’t the mainstream food system utterly contradict this?

What confidence can we citizens have in an industry and governmental agency that has up until now been complacent ethically, socially and environmentally?[xxvi]

Citizens who truly want to purchase items that reflect their ethical, social and political values would find it a challenge to have their needs met most days in the aisle of any supermarket. Combine that fact with the decline in consumption of meat or dairy, you could possibly have an industry issue. [xxvii] The solution for industry could be in the proposed regulation of the fashionable organic brand. Is this the motive?

The assumption is that if business does it organically then they are doing it better. Some may actually achieve this, which has to be a good thing. But by now I hope you have realised that if that business has to operate under the existing system of agri-food production then the answer is not necessarily so. You have only to look at the USA who have regulated organic since 1997 to see the problems we are likely to face.

USDA’s slippery organic slide

“...organic is at a crossroads. Either we can continue to allow industry interests to bend and dilute the organic rules to their benefit, or organic farmers – working with organic consumers – can step up and take action to ensure organic integrity into the future.” So said Francis Thicke in his article ‘What does organic mean’[xxviii]

Who owns organic in the USA, who will the industry leaders be in NZ?

Organics as a brand

It has been said that organics as a brand only works if you can get really rich, and of course you have to own it. So in the USA the first wave of acquisitions of organic processors was concentrated between December 1997 when the draft USDA standard was released, and its full implementation in October 2002. A second wave of acquisitions has been occurring since 2012. Few companies identify these ownership ties on product labels.

Who do the auditors work for?

Third-party regulatory certification usually undertaken by the likes of Biogro, Assure Quality, OFNZ as organic auditors will, say MPI, adopt a New Zealand standard which all agencies will have to comply with.

So who defines the word that defines the regulation?

There have been serious and frequent legislation problems thus far in the USA with a conflict of interest in the organic inspection programs [xxix] ranging from compliance lenience to erosion of standards as a result of large food corporations dominating membership of standard setting boards. [xxx] [xxxi]Governments either encourage or suffer extensive lobbying from business interests and this is evident in the changes in legislation at every term.[xxxii] Standards can be watered down and the definition of organic changes. Small producers are questioning the legitimacy of the organic certification system. [xxxiii] Egg production, hydroponics [xxxiv], artificial chemicals, quality of foods like baby food are some examples of the slippery slope the industry can successfully lobby for and get away with. [xxxv] [xxxvi] [xxxvii] [xxxviii] [xxxix] [xl]For years, an organic watchdog group, the Cornucopia Institute, [xli]raised questions about the rigor of organic enforcement. This year, however, amid reports of failures in several significant components of the industry, the program has faced a remarkable level of scepticism. Many have warned that gaps in enforcement of the "USDA Organic" label are eroding consumer faith. [xlii] There is no guarantee that the trade of organics is reliable either. [xliii] [xliv] [xlv] Food production too is necessarily diverse in the non-agribusiness way. It reflects local climates, soils, wildlife, pests etc, so any one size fits all model for organic regulation is potentially problematic. [vii] If you are operating on an industrial scale then regulation may suit you well, but not a one size fits all.

The backlash

There have also been serious concerns that the original organic small growers are being squeezed out .[xlvi] Hence the backlash that has now evolved since regulation, and the emergence of an alternative. [xlvii] [xlviii][xlix] [l] Regenerative organic, beyond organic aim to fill in the gaps in the current USDA organic rules. Alternative organic labelling is appearing. [li]Perhaps this is the future for New Zealand growers and producers who don’t seek an inferior organic certification. To some extent it is already happening at the alternative outside the system local level when grower meets customer. [lii] “Most of our farmers, at farmers markets go beyond the organic story, so they're exceeding those USDA organic certifications".[liii]

Converting food production to organics the traditional way is by far the preferential way of growing food and to encompass a holistic approach is central to its integrity. Government regulation that focuses on export trade and large scale food production is not compatible with this.

“Organic farming appealed to me because it involved searching for and discovering nature's pathways, as opposed to the formulaic approach of chemical farming. The appeal of organic farming is boundless; this mountain has no top, this river has no end.”

― Eliot Coleman, The New Organic Grower: A Master's Manual of Tools and Techniques for the Home and Market Gardener

The hurdle is for communities to challenge this global food, export policy bias that affects how we access food every single day of our lives. Incorporating organics within this framework yet managing to maintain its integrity will be a challenge for any enlightened government. I am not sure the Ministry of Primary Industries is the right organisation to handle this because of their conflict of interest with other agribusinesses.

Reclaiming the middle road

The words fresh and local now have a hollow sound to them as they are constantly repeated by the agribusiness producers and retail distributors. Time will tell if the same fate awaits the word organic.

Local food initiatives, organic or naturally grown, could benefit from regional and national support. Currently most food policy’s favour industrial production and trade of food. The organic regulations mooted certainly don’t appear to offer any encouragement to small food producers servicing their local area. In fact they appear to continue to operate at the expense of the local. Is a middle road possible? The most effective form of assistance could be regulation of the supermarkets. Support of local food initiatives could improve local food literacy, provide incentives for small food producers, shift the emphasis to diversified, low input production for local consumption, improve economic stability, encourage better healthier eating choices, provide for a healthy population and as we know when visiting our local farmers market provide an unparalleled social activity. A middle road incorporates the better aspects of all sides.

The question for New Zealanders is will MPI learn from our trading partners mistakes and ensure the word organic does not lose its meaning as it caters for industry.

Rise of the conscious consumer

The chair of OANZ says “We live in the age of the conscious consumer – a well-informed, instant sharing and caring, savvy, opinionated community that knows no borders.”

This global mindset is a 90’s anachronism. It has an agribusiness bias. It is questionable whether it reflects today’s conscious consumer at all. What may have seemed a good idea twenty years ago by supporters of organics has not taken into account the changes our food system has since undergone. We are now seeking naturally grown foods closer to home and we want to purchase our goods from people who have earned our trust.

We can only hope in the meantime that there won’t be any unfair burden falling on small scale enterprises because of any regulations aimed at problems caused by large scale production or for that matter any inclusion of farmers market in this agribusiness branding of the word. Local food enterprises need to distance themselves from this to retain any integrity.

If the USDA organic certification is watered down to an industry standard what hope is there for any integrity in the New Zealand organic regulatory system? [liv]

Keep your eye out for the opportunity to put in your submission to MPI in the next round sometime this year.

Grass roots initiatives keep it real

Ohoka Farmers Market reluctantly became independent earlier this year, resigning from the Farmers Market NZ organisation, after a great 10 year membership. We did so in protest of their accepting corporate sponsorship from agribusiness financier Rabobank.

Grass roots initiatives which aim to encourage and support local food enterprises in the region would also embrace the shift from global to local. To do so they encourage the diverse, independent, bottom up initiatives. They also provide a structural basis for community. Real food, a basic daily necessity, has the power of providing communities with a sense of connection. But to ensure the grass roots growth we have to be mindful of the agribusiness interest in it.

What can you do? The easiest way to make a difference is to be mindful about what you choose to eat. Keep supporting your local independent farmers market which consists of many individual food businesses. Make a submission at the next round of MPI talks. Talk to your local MP about independent local real food.

Thanks for reading, Barb (Ohoka Farmers Market Manager)

References and further reading:

[i] https://www.stuff.co.nz/business/103908345/lack-of-definition-risks-organic-products-being-mislabelled

[ii] http://newsroom.co.nz/2017/03/12/8521/millions-of-caged-eggs-sold-as-free-range-in-nz-supermarkets

[iii] http://www.stuff.co.nz/business/industries/9753438/Code-to-crack-supermarket-bully-tactics

[iv] https://www.nzherald.co.nz/nz/news/article.cfm?c_id=1&objectid=11201721

[v] https://thestandard.org.nz/advertising-standards-authority-rules-in-favour-of-greenpeace-ad-on-river-quality/

[vi] https://www.countdown.co.nz/news-and-media-releases/2017/august/countdown-fy17-annual-results

[vii] https://www.counterpunch.org/2017/12/11/what-does-organic-mean/

[viii] https://organicnz.org.nz/submissions/submission-on-an-organic-standard-in-new-zealand/

[ix] https://organicnz.org.nz/category/magazine-articles/

[x] https://www.consumer.org.nz/articles/majority-support-country-of-origin-labelling

[xii] https://www.stuff.co.nz/business/103908345/lack-of-definition-risks-organic-products-being-mislabelled

[xiii] http://www.rightlivelihoodaward.org/fileadmin/Files/PDF/Literature_Recipients/Ladakh/Norberg-Hodge_-_Globalisation_vs_Community.pdf

[xiv] https://www.localfutures.org/localization-a-strategic-alternative-to-globalized-authoritarianism/

[xv] https://www.auckland.ac.nz/en/about/news-events-and-notices/news/news-2017/01/food-industry-tactics-shape-public-food-policies.html

[xvi] https://rationalwiki.org/wiki/Vandana_Shiva

[xvii] https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2017/dec/04/animal-agriculture-choking-earth-making-sick-climate-food-environmental-impact-james-cameron-suzy-amis-cameron

[xviii] https://www.stuff.co.nz/life-style/well-good/motivate-me/94695382/why-new-zealanders-are-still-among-the-fattest-people-in-the-world

[xix] https://www.dw.com/en/hunger-is-a-political-problem/a-15459224

[xx] https://www.organicconsumers.org/news/agribusiness-and-climate-change-how-six-food-industry-giants-are-warming-planet

[xxi] http://www.eco-business.com/news/how-food-production-and-climate-change-are-intertwined/

[xxii] http://www.sustainabletable.org/869/impacts-of-industrial-agriculture

[xxiii] https://www.radionz.co.nz/news/national/280056/'supermarket-food-largely-unhealthy'

[xxiv] https://www.auckland.ac.nz/en/about/news-events-and-notices/news/news-2017/01/food-industry-tactics-shape-public-food-policies.html

[xxv] https://www.stuff.co.nz/environment/105373320/customers-call-out-companies-on-unnecessary-waste-and-use-of-plastic

[xxvi] http://newsroom.co.nz/2017/03/12/8521/millions-of-caged-eggs-sold-as-free-range-in-nz-supermarkets

[xxvii] https://www.stuff.co.nz/life-style/food-wine/100735629/The-average-Kiwi-eats-20kg-less-meat-amid-concerns-over-sustainability-of-agriculture

[xxviii] https://www.counterpunch.org/2017/12/11/what-does-organic-mean/

[xxix] Conflict of interest embedded in the organic inspection program. To win the "USDA Organic" label, farms need not undergo a review by government inspectors. Instead, farms hire their own inspection companies, or “certifiers,” to conduct the visits. Because organic farmers select their own inspection agency, a farmer who wants to keep hens confined need only hire one of the more lenient agencies.

[xxx] Erosion of the standards; Not unique to the USA many members of standard-setting boards come from large food corporations.[80] As more corporate members have joined, many nonorganic substances have been added to the National List of acceptable ingredients.[80] The United States Congress has also played a role in allowing exceptions to organic food standards. In December 2005, the 2006 agricultural appropriations bill was passed with a rider allowing 38 synthetic ingredients to be used in organic foods, including food colorings, starches, sausage and hot-dog casings, hops, fish oil, chipotle chili pepper, and gelatin; this allowed Anheuser-Busch in 2007 to have its Wild Hop Lager certified organic "even though [it] uses hops grown with chemical fertilizers and sprayed with pesticides."[81][82]

[xxxi] Objections from some of the largest egg operations — including Herbruck's — and two key Capitol Hill advocates appear to have stalled the proposal. Farm groups representing large conventional agricultural companies have also objected to these requirements.

[xxxii] In May 2018 , the Trump administration further delayed the implementation of the proposal for six more months, “to allow time for further consideration,” a move that many see as a prelude for dropping the regulation permanently.

[xxxiii] Unfortunately, consumers have no idea what they’re getting with ‘USDA Organic’ anymore.”

Organics as brand only works if you can get really rich, and of course you have to own it. So in the USA the first wave of acquisitions of organic processors was concentrated between December, 1997 when the draft USDA standard was released, and its full implementation in October, 2002. A second wave of acquisitions has been occurring since 2012. Few companies identify these ownership ties on product labels.1

“Perhaps we shouldn’t be surprised to find that big business is taking over the USDA organic program because the influence of money is corroding all levels of our government,”

[xxxiv] https://www.counterpunch.org/2017/12/11/what-does-organic-mean/

[xxxv] United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) on Monday announced its intention to officially withdraw the Obama-era livestock rules that would have strengthened animal welfare requirements for organically certified meat and dairy.

[xxxvi] Hydroponics, aquaponics and aeroponics growers can earn organic certification. All three techniques involve growing crops without soil, also called hydroculture. For eight years, laws were in place, but different parts of the industry interpreted the laws differently, and the USDA didn’t rush to clarify the issue.

[xxxvii] Organic advocates are also calling for a ban on questionable practices such as allowing ingredients in organic products derived from “mutagenesis” (using chemicals or radiation to genetically mutate life forms), treating animals on organic farms with genetically engineered vaccines, the spraying of the antibiotic streptomycin on organic apples and pears, and the little-known loophole in organic standards allowing the injection of antibiotics into newborn chicks

[xxxviii] As Lynne Curry wrote in her thorough backgrounder, the language in the current organic standards that govern animal welfare is pretty loose the definition of “outdoors” sounds pretty straightforward to laymen. But those terms, as it turns out, are rather loose, and inherently more about birds-per-foot than how you quantify air and sky.

The responsibility for regulating the industry lies with USDA's National Organic Program, which defines what farming methods count as organic and issues certificates to farmers and handlers that comply with those rules. Those certificates allow those farmers and handlers to sell food as "organic." The organic label enables them to charge as much twice the price of a conventional product.

[xxxix] Under USDA requirements, organic livestock are supposed to have access to the “outdoors,” get “direct sunlight” and “fresh air.” The rules prohibit “continuous total confinement of any animal indoors.” Organic livestock are supposed to be able to engage in their “natural behaviour,” and for chickens, that means foraging on the ground for food, dust-bathing and even short flights.

Rules are much less stringent than many consumers think: a henhouse can be deemed “USDA Organic” even if it holds 180,000 birds who are not allowed outside and are kept at a density of three hens per square foot of floor space. In a follow up decision, the USDA ruled that the animals in “organic” products need not be treated any more humanely than those in conventional farming.

The USDA allows Herbruck's and other large operations to sell their eggs as organic because officials have interpreted the word “outdoors” in such a way that farms that confine their hens to barns but add “porches” are deemed eligible for the valuable “USDA Organic” label. The porches are typically walled-in areas with a roof, hard floors and screening on one side.

As for how densely organic livestock may live, the USDA rules do not set an explicit minimum of space per bird.

Similar concerns for animal welfare have spurred the demand for organic eggs, which are supposed to come from birds that are not only cage-free but also allowed outside. About 12 percent of grocery store expenditures for eggs goes toward those labelled USDA Organic, and many buyers appear to think the hens are allowed out.

Unapproved Ingredients Make it into Baby Food? Chemical additives have skirted USDA approval and made their way into infant formulas – some of which even bear the USDA Organic Seal! This confirms that even organic certification is NOT watertight.

Last December, the U.S. National Organic Standards Board, an expert panel that advise the USDA Secretary on organic matters, narrowly approved Martek Biosciences Corporation's petition to allow the use of their genetically modified soil fungus and algae as nutritional supplements in organic food.

[xli] https://www.cornucopia.org/2018/06/organic-industry-watchdog-asks-doj-regulators-to-examine-organic-poultry-acquisition/

[xlii] According to the inspector general: “The USDA “was unable to provide reasonable assurance that … required documents were reviewed at U.S. ports of entry to verify that imported agricultural products labelled as organic were from certified organic foreign farms."

Chapman said. “This is not just a few bad eggs. Unfortunately, consumers have no idea what they’re getting with ‘USDA Organic’ anymore.”

[xliii] As much as half or more of some organic commodities are imported, and in a September audit, the Inspector General of the USDA revealed that bogus “organic” products from overseas could easily get into the U.S. undetected.

[xliv] https://www.cornucopia.org/2008/01/wal-mart-organics/

[xlv] “Perhaps we shouldn’t be surprised to find that big business is taking over the USDA organic program because the influence of money is corroding all levels of our government,” Thicke said at the October 24, 2017, meeting, according to a transcript. “At this point, I can see only one way to bring the organic label back in line with the original vision of organic farmers and consumers. We need an add-on organic label for organic farmers who are willing to meet the expectations of discerning consumers who are demanding real organic food.”

[xlvi] Combined with the fact that food retail sales are sold predominantly through high volume distribution channels such as supermarkets, the concern is that the market is evolving to favour the biggest producers, and this could result in the small organic farmer being squeezed out.(wiki)

[xlvii] Organic practices were pioneered and promoted by farmers and stakeholders not politicians. This has resulted in a back lash to the industry focussed organic industry.

[xlviii] It has been claimed that organics success in the USA threatens to eclipse its activist orgins, some of its original promoters seek to reclaim it.

[xlix] https://newfoodeconomy.org/third-party-food-certifications/

[l] https://www.cornucopia.org/farmers-market-guide/

[li] https://modernfarmer.com/2018/03/the-real-organic-project-alternative-organic-label/

[lii] Several farm groups are, out of frustration, creating alternatives to the “USDA Organic” label. Most prominently, the Rodale Institute, a key early supporter of the “USDA Organic” label, and Patagonia, the apparel maker, and real organic project. Promoting a new “regenerative organic” standard will fill in gaps in the current USDA organic rules.

Other ref and links of interest:

http://dig.abclocal.go.com/kgo/PDF/Meat_Labels.pdf

https://www.ecowatch.com/10-reasons-consumers-buy-organic-1881899943.html

//www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24968103

[liii] https://www.sfchronicle.com/news/article/Indiana-s-farmers-markets-give-a-boost-to-small-13036720.php

[liv] https://www.usda.gov/media/blog/2012/03/22/organic-101-what-usda-organic-label-means

[i] https://www.commondreams.org/views/2001/06/03/organic-industrial-complex